If last year’s edition of The Best Buddhist Writing was the most Asian volume published to date, then this year’s volume is a return to normal.

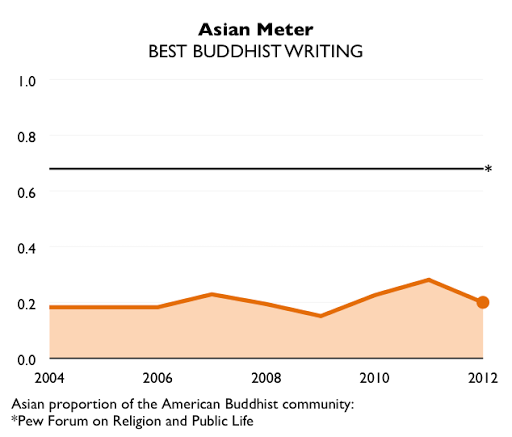

For the past nine years, Melvin McLeod and the other Shambhala Sun editors have gathered into a single book “a thought-provoking mix of the most notable and insightful Buddhism-inspired writing published in the last year.” On average, six or seven Asian writers make it into the volume, which translates to a ratio of about one in five. This year is perfectly typical with six Asian writers at a ratio of exactly one in five. That’s not many when you consider that more than three-in-five American Buddhists are Asian.

I had hoped that last year’s exceptional number of Asian writers would mark the start of a new normal. Compared to The Big Three print magazines, The Best Buddhist Writing historically includes a higher proportion of Asian authors. The editors even highlighted their awareness of diversity issues last year when they organized a Buddhadharma forum titled, “Why is American Buddhism so White?” Maybe there wasn’t much good Asian writing to be found this year. Maybe 2011 was a fluke.

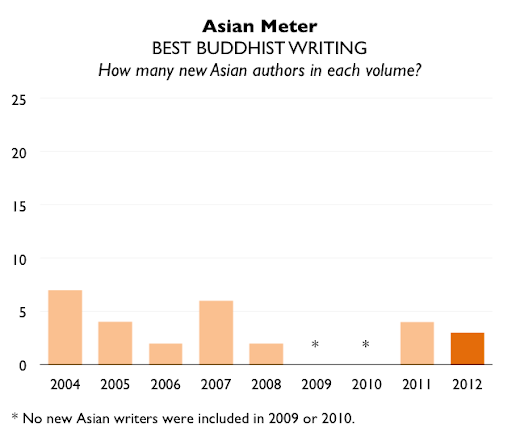

The editors at least managed to find new Asian writers, unlike the two years when the only Asian authors included where those who had been published in previous volumes.

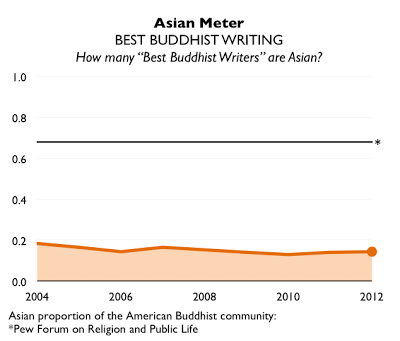

If Asian Buddhist writers are to be better represented in The Best Buddhist Writing, then the yearly number of new Asian authors will have to grow. This shift will be reflected in the measure of “Best Asian Writers”—those who have ever been published in The Best Buddhist Writing—as a proportion of the total lot of “Best Buddhist Writers.” Since the series’ inception in 2004, this proportion has declined from less than one in five to now just one in seven.

In other words, new non-Asian writers have been included in The Best Buddhist Writing at a greater frequency than Asians have been.

For The Best Buddhist Writing to meaningfully include more Asian writers, the editors could include in each volume the writing of four Asians who had not been included in any previous edition. That’s just one more than the three new writers who are currently added on average each year. Of course it means that more work would need to be done to find that worthy piece of writing. My hunch is that as the Shambhala Sun editors get more used to seeking out good writing by Asian authors, they will develop sharper intuitions on where to look and they’ll find some more promising work along the way.

We’ll see how The Best Buddhist Writing turns out next year. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy The Best Buddhist Writing 2012.