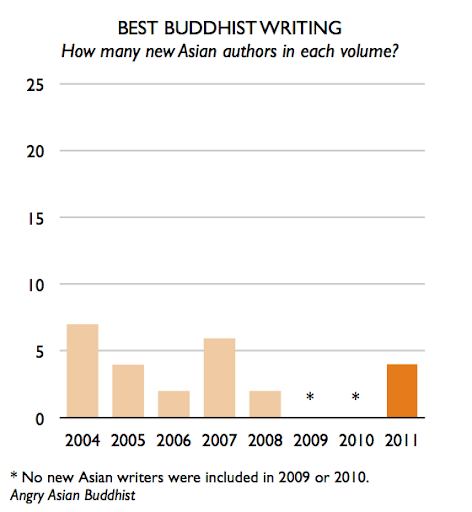

On the last Asian Meter update, Adam asked about the dynamics that underlie the small number of bylines that TheBigThree set aside to Asian writers.

So, why do you think that is? Is it just blatant racism, or are there other factors? How many Asian writers have submitted material/applied for positions at The Big Three? How do they source their writers and material?

I responded separately that I believe this pattern to be a case of institutional racism, rather than “blatant” racism (such as an informal policy or a consciously implemented prejudice). This question is explored in more detail on an old post at Dharma Folk.

The second part of the question speaks to the submission process—we know the output, but what about the input? This question has been asked several times before and is worth revisiting. Below I’ve provided a similar comment that Ashin Sopaka left a long while ago.

While I do not in any way invalidate your experience of racism in Buddhism (I myself have seen negative comments like “ethnic Buddhists”), I can’t help but wonder how many Asian American (AA) Buddhists are stepping up to the plate, applying for jobs or submitting articles to the referenced publications, asking to be involved in panel discussions, etc. If this is happening and AAs are being actively excluded, then indeed, this is racism at its ugliest. Or, are AAs sitting back and waiting to be invited/involved? Or are AAs refusing the invitations due to language barriers, or whatever other reasons?

The logic here is straightforward. Perhaps this inequality is of the marginalized groups’ own making—there are fewer Asian writers because fewer Asians submit articles. This point was addressed directly by another blogger.

Ashin[hpoya], I can answer that one for you. These publications don’t think to ask Asian-Americans, so Asian-Americans are rarely if ever extended an offer to refuse in the first place. It’s not that Asian-Americans aren’t stepping up, it’s that there is a network of white convert Buddhists entrenched in the publishing field and they reach out to print articles by and about other people like themselves, without stepping out of their bubbles or making serious attempts to include other voices.

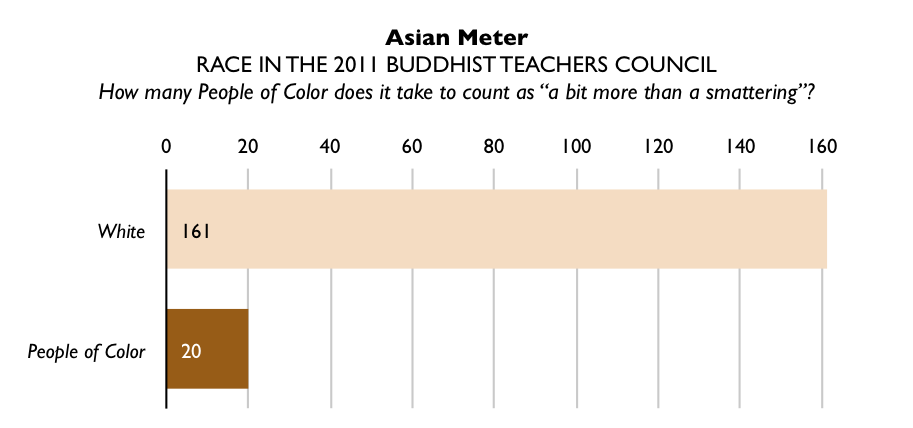

Some of this has to do with race issues in publishing. The staff at these magazines is virtually all white and always has been. That is not unusual in the publishing world, but it is regrettable at publications that seek to represent a religion that is overwhelmingly non-white (and even English-speaking Buddhists are less than 50% white). It isn’t racism in terms of actively disparaging non-whites. It is white privilege, the privilege to be focused only on one’s own community, to believe one’s own community is representative of the whole, and to not ever have to think about how one’s whiteness allows smooth entrance into the world of publishing and speaking for Buddhism in a way that people with far more history with Buddhism (but far more melanin as well) are as a group unable to access (the occasional individual exception doesn’t invalidate the general rule here).

Mr. Boyce’s article and his shock at how it was received are typical of this pattern. A person of presumably no malicious intent, he was simply blind to how his decisions wound others–blind because his skin color and social privilege allow him to not have to think about such issues until someone blows up at him after the fact. This is not racism as outright hatred, but institutionalized racism that affects the whole society and is especially entrenched in the media (i.e. the industry of representation and normative information control), Buddhist magazines included.

This response cuts right into the interwoven threads of opportunity, incentives and that pernicious elephant on the dining room table: white privilege. While hinging on white privilege, what’s key is how this privilege increases both opportunities and incentives for white writers at the expense of People of Color.

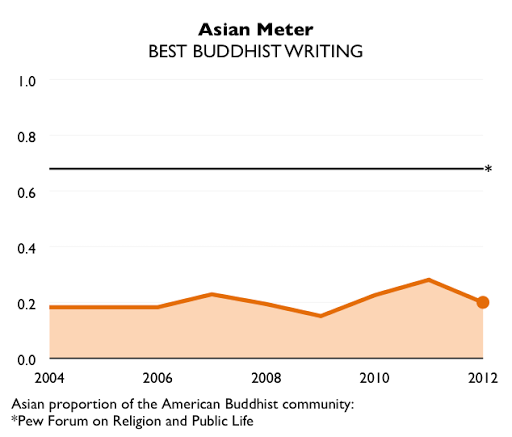

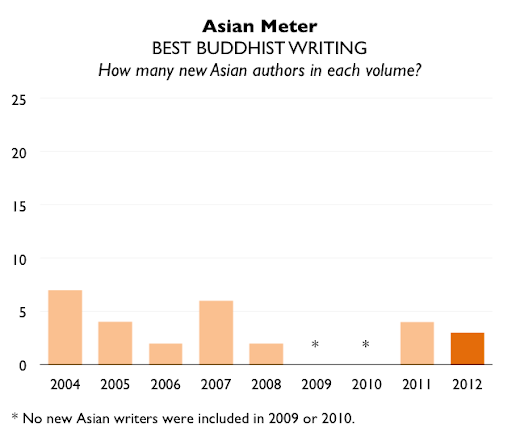

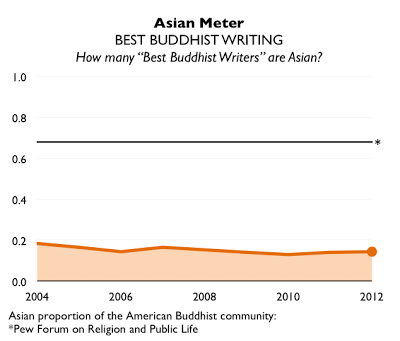

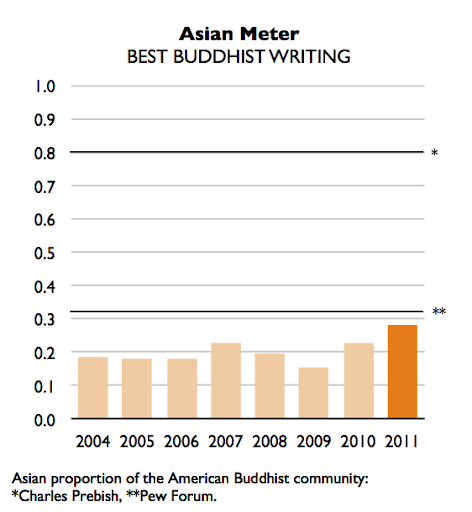

The Asian Meter merely puts some casual observations to the test with systematic inquiry. How many Asians actually write for The Big Three? Adam’s question goes further and points in the direction of what’s going on behind the scenes here. What are all the players doing? The answer to his question is more complex, and it’s exactly the sort of question we need to be asking in order to effectively address racial imbalances in our publications.

For example, in creating the Asian Meter database, one of the key factors I noticed has to do with the composition of a magazine’s regular contributors. If you are a white writer, you’re more likely to be tapped to write again in Tricycle than if you happen to be Asian. (I don’t have the numbers in front of me right now, but I’ll happily dig up the numbers for another post.) One solution might be for Tricycle to do more outreach both to recruit new Asian writers and also to retain old ones. But I’m getting ahead of myself here—it’s only by looking deep into the issue that we have the empirical basis to act on such a suggestion.

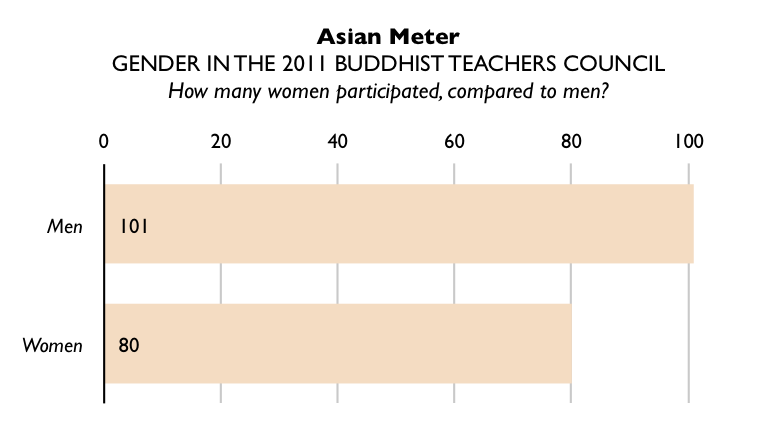

I haven’t provided a very thorough response, but Adam’s question has no simple answer. Just think of when we ask the same type of question in other fields. Why do so few women become surgeons? Why do so few African American students sign up for business plan competitions? It is no less controversial to ask why so few Asians write in the major American Buddhist publications. But it’s my belief that questions like Adam’s are among the few ways we can make any progress towards a truer diversity.