What’s gender got to do with Buddhism? How are women—and men—working with the challenges of sexism in Buddhist institutions? What opportunities present themselves when women pursue the path of dharma outside of traditional institutions and organizations? With these questions—and more—we are welcomed into Buddhadharma’s Winter 2010 feature, “Our Way.”

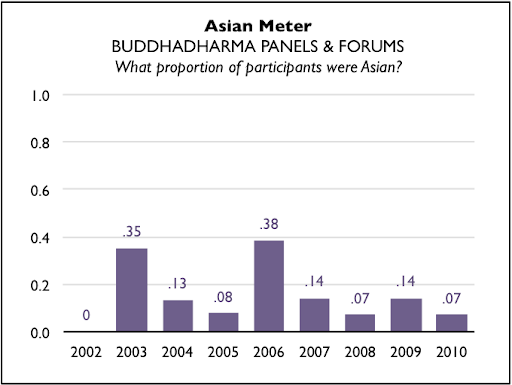

Brought together to discuss these questions are the brilliant minds of Grace Schireson, Christina Feldman, Lama Palden Drolma, Rita Gross, Lama Tsultrim Allione, and Joan Sutherland. These authors delve into the history of women bringing balance to the Buddhist community, current forward-moving trends and the outlines of a more equitable future for us all. But apart from these great women and their compelling discussion, I found something missing.

Namely, Asians.

In fact, no People of Color were included in this list—but here I prefer to underline the most blatant omission. For a feature that focuses “on women and Buddhism”—the editors chose none to represent Buddhism’s largest demographic: Asian women. Even when we narrow our purview to the Buddhist community in the “West,” Buddhists of Asian heritage are still an obvious part of the picture. Our voices are Western voices. Our mothers, sisters and daughters also reside in these lands, attend Western schools, live by Western rules, embrace Western values and grapple with the pernicious challenges of patriarchy that so regrettably pervade time and border. Asian American Buddhist women even represent the State of Hawai‘i in the U.S. House. By charting “Our Way” with the voices of white women, Buddhadharma has chosen to displace Asian women from “our” discussion.

Keep in mind that there are plenty of Asian Buddhist women capable of delving into these questions. The editors could easily have contacted Mushim Ikeda-Nash, Rev. Patti Usuki, Ven. Tenzin Kacho or Anchalee Kurutach, women of varied backgrounds who are engaged Buddhists and also Asian American. (In fact, you can even listen right now to two of them talk about Buddhism in the United States—in an all-Asian American broadcast to boot!) All that said, when it comes to Shambhala Sun’s track record at bringing Asians into the conversation, they’ve made it clear that, well, we’ve just about got a Chinaman’s chance.

My laments have become so frequent that they are banal. Only last month I admonished Shambhala Sun Space (among others) for covering white non-Buddhist politicians, while completely ignoring non-white politicians who are actually Buddhist. Two years ago, I excoriated Buddhadharma for deliberately excluding Asian Americans from a forum on “the future of Buddhism in a post-baby boomer world.” We can even look back to Beneath a Single Moon, Shambhala Publication’s anthology of contemporary Buddhist poetry, which failed to include a single Asian American Buddhist poet. Keep it up, and I’ll be able to publish an anthology of my own—a record of Asian Americans’ marginalization by the white Buddhist establishment.

If any of this is news to you, welcome to the discussion. Concerning the key actors involved, however, no new ground has been covered. We all know this dance. Angry Asian Buddhists castigate the white-privileged editors—who in turn acknowledge their faux pas, bemoan their obliviousness and profess their love for equality. Who knows, they may even ask for a letter to the editor. How grand!

But what would it take to have real change? How do we get consideration for a seat on that next panel—and how do we avoid being Chinatowned into a group of Asians talking about some “Asian” topic? I assure you, we Asian Buddhists can do a lot more than iron your clothes, paint your nails and serve you our “ethnic” food. We can talk about individual struggles, community institutions and transformative frameworks. I work with white Buddhists (and other Buddhists of color) all the time out here in the field, but I wonder what it takes to hang with the white kids in the big leagues.

Many of the divisions in the Buddhist community cannot be healed overnight. As one simple step, publications like Buddhadharma could simply recognize the broader diversity that exists. There are few starker lines of the so-called “ethnic divide” than the refusal of white Buddhists to even acknowledge the voices of the Asian Buddhist majority in the West.