Released in 1991, Beneath a Single Moon: Buddhism in Contemporary American Poetry was the first anthology to highlight the poetry of practicing American Buddhists. The reaction of the Asian American writing community was for the most part simple and straightforward. We were less than happy. Of the 45 American poets who appeared in Beneath a Single Moon, some were well-known poets, while others were quite obscure. None were Asian American.

Mushim Ikeda-Nash remembers “dropping the book as though it had burnt me.” In PREMONITIONS: The Kaya Anthology of New Asian North American Poetry, editor Walter Lew provided half a dozen examples of accomplished Asian American poets whose work should have qualified. In 1997, Juliana Chang, Walter Lew, Tan Lin, Eileen Tabios, and John Yau together lambasted Beneath a Single Moon editor Kent Johnson in the Boston Review, arguing that his anthology “displaces Asian American poets from the practice of Buddhism.” They reprinted Lew’s most polemical paragraph from PREMONITIONS.

The 45 American poets whose essays and poetry on Buddhist practice comprise the anthology are all Caucasian, and the book only mentions Asians as distal teachers (ranging from Zen patriarchs to D.T. Suzuki), not as fellow members or poets of the sangha . . . When one considers the relative obscurity of some of the poets included in the book, one wonders how it was possible not to have known the Buddhistic poetry of such writers as [Lawson Fusao] Inada, Al Robles, Garrett Kaoru Hongo, Alan Chong Lau, Patricia Ikeda, and Russell Leong. . . . [Gary] Snyder’s introduction deliberates the question—‘Poetry is democratic, Zen is elite. No! Zen is democratic, poetry is elite. Which is it?’ . . . perhaps he should have also asked whether Zen and poetry, as reconfigured in American Orientalism, are racist.

Kent Johnson did little to help the situation when in a 1997 email response, he backhandedly disqualified all the writers Lew had mentioned.

Before reading this quote, I was quite certain that we had probably missed, out of ignorance, Asian-American poets who should have been included in the anthology. But now I am not as sure. If Mr. Lew (and the other co-signers of the BR response) had carefully considered the Shambhala anthology, they would have seen that a fundamental criteria for inclusion was a serious background in Buddhist study and practice. We were not interested, in the least, in poetry exhibiting the vague and stereotypical waft of the “Buddhistic.” If anything, our anthology begins to point to the fact that reductive notions of the “Buddhistic” are one of the by-products of the “Orientalism” that Mr. Lew denounces. There is simply no way of boiling down Buddhist artistic expression to any particular “Buddhistic” characteristics of tone, content, or style.

Now, I still suspect that there are publishing Asian-American poets who would have met the criteria we established for the anthology, but their absence was certainly not due to some underlying racist criteria of selection; we simply (and perhaps to our editorial discredit) were, and are, unaware of Asian-American poets who also happen to be Buddhists. Apparently, and unfortunately, so is Mr. Lew, as I assume he would have mentioned specific names if there were any.

Preoccupied with the word “Buddhistic,” Johnson failed to verify that most of the writers mentioned by Lew were, in fact, practicing Buddhists. One of these writers played a major role in getting me involved in the Buddhist community. Little did I know that, at the very time he advised me on Buddhist engagement, this literary controversy was storming in the background.

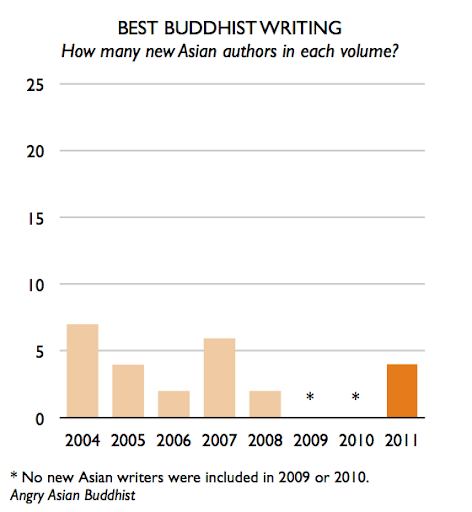

It took me some time to piece this history together, emailing friends, hunting down references and reviewing email exchanges from, well, the last century. What you see here is a sample of a much more complex fabric of conversations being woven at the time. On the face of it, the recriminatory exchanges must have seemed futile, either side barely acknowledging the other’s argument. But these conversations were not entirely in vain. As discussed by Jonathan Stalling, subsequent anthologies of Buddhist poetry opened their pages to include Asian American authors, including those mentioned by Lew.

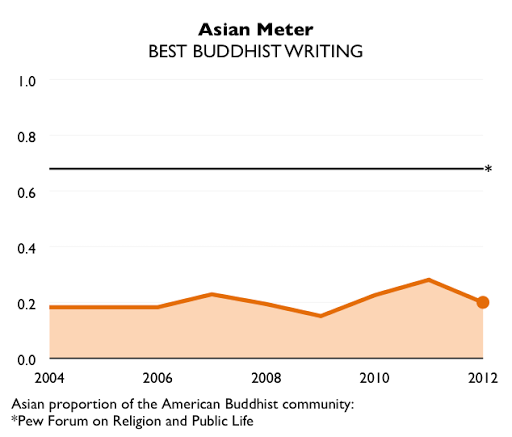

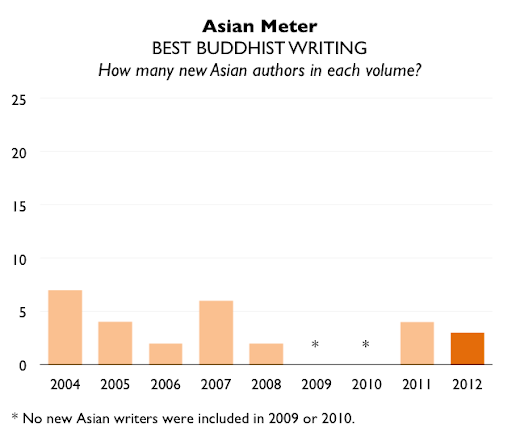

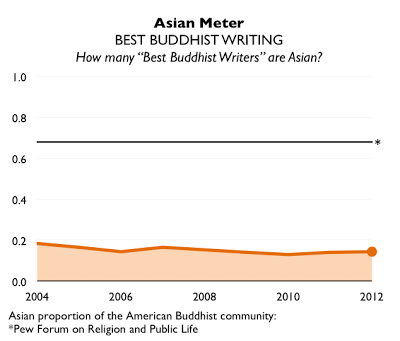

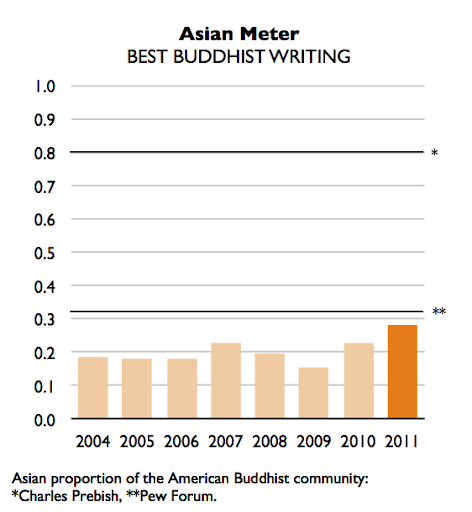

Reflection on this history brings me an even share of bitterness and comfort. The bitterness is in seeing that so little has changed—that two decades after the publication of Beneath a Single Moon, the nature of the controversy and the criticism it engendered could have happened just last month. In fact, it did. On the other hand, the comfort is in knowing that I’m not alone, that I’m following in the footsteps of many others who came before me. There is comfort too in the thought that, if history is any guide, change may indeed come.