Buddhist Asian Americans are often surprised to encounter so many stereotypes about us. For all the claims we mostly keep to ourselves in “ethnic enclaves,” there seems to be a rather thorough set of stereotypes about people whom most white Buddhists claim to barely know. Worse yet is that these stereotypes are routinely cited as solid facts.

The stereotypes are generally about how different we are from “American Buddhists.” These might sound familiar: We Buddhist Asian Americans are basically immigrants. We cannot speak English and carry a more supernatural bent. We focus our energies into holidays and spiritual beliefsinstead of meditative practices. We really “place little emphasis on meditation.” Some of us are Oriental monks who bring our exotic teachings to the West. The temples we attend aren’t about spreading the Dharma—they’re just ethnic social clubs. I could go on.

These stereotypes fall into two or three categories. You are probably most familiar with the Oriental Monk and the Superstitious Immigrant, but there’s another emerging icon that I’ve seen with increasing frequency: the Banana Buddhist. Call it a typology of Asian American Buddhist stereotypes—or a stereotypology, if you will.

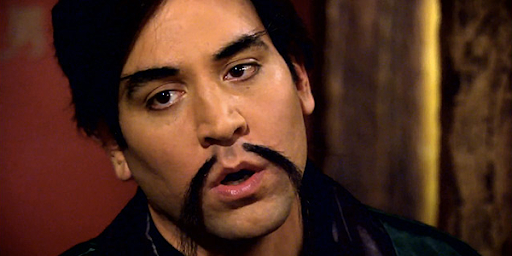

He came from Asia, where he became an authority in authentic Buddhism sometime in the distant past. He has no family to hold him down, so he’s come here to be your guru. He’ll sit in the zendo, cross-legged in his Oriental robes, and teach you in his accented English that “authenticity” resides in your heart, not in what you say or do. Sure, there’s a lot about the modern world he isn’t familiar with, but that’s fine because his sole purpose is to pass along the authority and authenticity of his teachings so that you can make Buddhism better, more modern and more relevant in a way that he frankly never could.

She came here from some war-torn Asian country and settled down in a nice little ethnic enclave with other people like her. Not only does she believe in gods and spirits, she prays to them daily to ensure that her kids get top-notch test scores. Oh, sure she may “speak” English, but only just barely. You pretty much already know what she thinks and believes about Buddhism—what you don’t know of what she thinks you can look up online or isn’t going to be real Buddhism anyway—so why bother to even ask? Just take some photos of her around the temple with your DSLR. You can sell those photos to Tricycle.

She’s basically a white person who happens to be Asian. She speaks English surprisingly well and barely a word of whatever Asian dialect her parents spoke. She cooks non-ethnic food, uses the dishwasher and crosses her chopsticks. She may have been raised by Superstitious Immigrant, but she’s renounced that backwards and foreign worldview. She probably doesn’t even identify as Asian. You can find her at yoga Thursdays and your zendo’s weekend sits, where she’ll sit quietly in the back and not make much of a fuss. It really doesn’t matter if she doesn’t speak up because whatever she says isn’t going to be any different from what the white Buddhists are saying.

Remember, I’m listing stereotypes, not describing Buddhist Asian Americans. These stereotypes’ salient characteristics are rooted in what has been said and written about us and are often taken as fact by those with limited exposure to the real diversity of Buddhist Asian Americans. After all, most of us are neither Oriental Monk, Superstitious Immigrant or Banana Buddhist—although some of the characteristics may pick at our insecurities. (I use the dishwasher.)

It’s important to be mindful of these stereotypes and how they shape our own perceptions. If you choose to think of us as Superstitious Immigrants, you will never accept us as real Americans. If you choose to think of us as Banana Buddhists, you then trivialize the value of our heritage. The best way to uproot these stereotypes is first to stop perpetuating them, to encourage others to stop perpetuating them, and then to actually start spending some more time getting to know Buddhist Asian Americans for who we really are.

Archivist’s Note: Comments have been preserved from the original website for archival purposes; however, comments are now closed.

AnonymousMay 1, 2014 at 8:45 AM

Wow, this isn’t something that I’ve actually reflected on before.. I’m glad you’ve brought this up. This makes me think of the disclaimers I make when I tell people I’m Buddhist in taking into consideration the judgments I think they’re making of me as an Asian American Buddhist.

And the first and foremost disclaimer that comes to mind when I tell people I’m Buddhist is that I don’t do “that superstitious stuff”, like burning money or asking for miracles. And I think I make that disclaimer in reaction to the fear in the back of my head of being assumed as the stereotype of the “superstitious immigrant”. This is something I’ve experienced in both the U.S. and now in Taiwan, where many the only exposure many folks have had to Buddhism, through direct experience or indirect (like the media), in connection with superstitious practices, and that ends up being their impression of what Buddhists practice.

I will admit that I’ve always had a hard time understanding my father’s Buddhist identity as anything other than “the superstitious immigrant” until I began to incorporate Buddhism explicitly into our usual conversations. I would say things like “Well I learned from Buddhism that…” and I’ve found that he’s also picked up on that and has connected his Buddhist practice things in everyday life beyond the occasional superstitious practices that I remember learning from my father during my childhood. That’s not to say those superstitious practices are not a core part of his practice – it’s just that I’ve found his Buddhist practice to be more complex than what I had pre-labeled him as. It’s actually really nice to have found a small part of our Buddhist practice that we can actually agree on.

AnonymousMay 19, 2014 at 11:40 AM

This is a great post and a good conversation.

@ektesol: my wife is from Japan, and went through the same kind of thought process as you did re: superstitious Buddhists, but as the years went on and I became more famliar with the culture, I started to make the same kind of connection. Like you said, I began to realize that Buddhism in Asian culture is a complex and nuanced thing and I had basically just given it a blanket judgment based on limited information.

Glad to see others had the same experience.

AnonymousMay 19, 2014 at 11:43 AM

Sure, there’s a lot about the modern world he isn’t familiar with, but that’s fine because his sole purpose is to pass along the authority and authenticity of his teachings so that you can make Buddhism better, more modern and more relevant in a way that he frankly never could.

Being a convert Buddhist, this one really hit home for me too. I’ve definitely done my fair share of “modernizing Buddhism”.

UnknownSeptember 14, 2015 at 9:18 AM

Hi there! I’m an Asian-American Buddhist as well, and I have been leading a Sunday Buddhist group for about a year now. We have quite a few American Buddhist practitioners that come here weekly, so I’m wrote familiar with the western view of Buddhism vs traditional Eastern Buddhism.

Just want to point out to the above comment that burning money is definitely not part of Buddhism. It may have become part of the culture through Daoist temples, where people group all the deities, like Guan Yin and Confucius, spirit protectors etc. together and made it a place to ask for favors and good fortune. But it definitely is not part of the Buddha’s teachings.

I also havea faint idea of the stereotyped your described. However, being in the Midwest, people barely know any Asians, much less Buddhist Asians, so there’s less of the prejudice here. People are quite accepting here because they’re eager to learn about Buddhism.

We have an eclectic mix of people from different backgrounds here in our group, from Vietnamese to Chinese to American, and everyone eats together and have a pleasant time. I’m really proud of how everyone can come together through a shared belief, and not be limited to culture or ethnicity.

True Buddhism, I think, is never limited to one culture. It should adapt to the needs of the people in specific places and times. The Buddhism we teach had influences from Eastern Mahayana Pureland and Zen school, to some Vajrayana. There’s even some Theravada, but it is not our focus. The core of Buddhism is the same, and ultimately, all roads lead to Rome.

Hope that western Buddhism can embrace now diversity… But perhaps they’re also trying to adapt Buddhism to their own needs too, outside of the supernatural element they may find hard to accept from the eastern tradition. I think more study of the scriptures and actual practice can help bridge that gap, as well as inviting Asian practitioners to share their experiences.

Cara LiuSeptember 14, 2015 at 9:20 AM

Hi there! I’m an Asian-American Buddhist as well, and I have been leading a Sunday Buddhist group for about a year now. We have quite a few American Buddhist practitioners that come here weekly, so I’m wrote familiar with the western view of Buddhism vs traditional Eastern Buddhism.

Just want to point out to the above comment that burning money is definitely not part of Buddhism. It may have become part of the culture through Daoist temples, where people group all the deities, like Guan Yin and Confucius, spirit protectors etc. together and made it a place to ask for favors and good fortune. But it definitely is not part of the Buddha’s teachings.

I also havea faint idea of the stereotyped your described. However, being in the Midwest, people barely know any Asians, much less Buddhist Asians, so there’s less of the prejudice here. People are quite accepting here because they’re eager to learn about Buddhism.

We have an eclectic mix of people from different backgrounds here in our group, from Vietnamese to Chinese to American, and everyone eats together and have a pleasant time. I’m really proud of how everyone can come together through a shared belief, and not be limited to culture or ethnicity.

True Buddhism, I think, is never limited to one culture. It should adapt to the needs of the people in specific places and times. The Buddhism we teach had influences from Eastern Mahayana Pureland and Zen school, to some Vajrayana. There’s even some Theravada, but it is not our focus. The core of Buddhism is the same, and ultimately, all roads lead to Rome.

Hope that western Buddhism can embrace now diversity… But perhaps they’re also trying to adapt Buddhism to their own needs too, outside of the supernatural element they may find hard to accept from the eastern tradition. I think more study of the scriptures and actual practice can help bridge that gap, as well as inviting Asian practitioners to share their experiences.

Ambellina AmoryDecember 26, 2015 at 7:16 AM

I’m naive. Before reading this, I had no knowledge that people made these assumptions about Asian-American Buddhists. I think one of the most important things about following a religion is to learn from others constantly. Perpetuating stereotypes is the result of ignorance and an unwillingness to learn. Converts to Buddhism should be aware of and learn about the diversity of cultures that have practiced this religion for centuries. That way, they can enrich their perspective and their own practice and study.

Ambellina AmoryDecember 26, 2015 at 7:17 AM

I’m naive. Before reading this, I had no knowledge that people made these assumptions about Asian-American Buddhists. I think one of the most important things about following a religion is to learn from others constantly. Perpetuating stereotypes is the result of ignorance and an unwillingness to learn. Converts to Buddhism should be aware of and learn about the diversity of cultures that have practiced this religion for centuries. That way, they can enrich their perspective and their own practice and study.